I Feel So Much More Knowledgeable Now

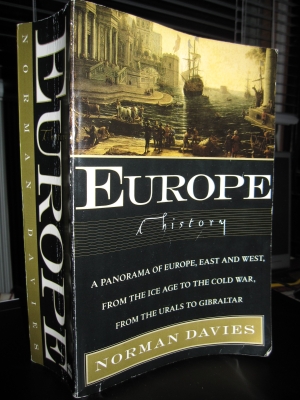

I bought Europe: A History about a year ago due to prodding from someone obviously more well-read than I am. Even though I started reading it immediately, I only finished it yesterday. Yes, I read other books in the past year — shut up. 1100+ pages of text — and dozens more of maps and charts and lists — later, and I feel like I have a nice foundation to delve further into European history. But a foundation is all it is — it’s tough to go in-depth when you’re attempting to write about the entirety of human history across a whole continent.

I bought Europe: A History about a year ago due to prodding from someone obviously more well-read than I am. Even though I started reading it immediately, I only finished it yesterday. Yes, I read other books in the past year — shut up. 1100+ pages of text — and dozens more of maps and charts and lists — later, and I feel like I have a nice foundation to delve further into European history. But a foundation is all it is — it’s tough to go in-depth when you’re attempting to write about the entirety of human history across a whole continent.

This is the type of book teenagers be should reading, and I wish I read it a lot sooner myself. It covers everything from the spread of agriculture thousands of years ago to ancient European civilizations — and not just Ancient Greece or Rome — to the Enlightenment to the Partitions of Poland to the end of the Cold War (I just restated the subtitle of the book in a longer statement). And since it’s such an immense and comprehensive tome, it opens up the entire history of Europe to the reader, allowing them to discover which events or periods they find most interesting. In that way, it acts as a catalyst for more focused reading.

At least that’s the effect it’s had on me. I have already started on a Dostoevsky binge, kicking off with a quick re-read of Notes From Underground. I’ll then move on to the big guns: Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov. Maybe I’ll read The Idiot in between those two, to maintain chronological order to appease the OCD aspect of my brain. I also have quite a bit more motivation to read through The Battle: A New History of Waterloo and the Memoirs of Napoleon’s Egyptian Expedition, 1798-1801, two gifts I received from a history buff. Most of all, I want to get through yet another massive tome, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, which was another gift; I’m just not ready to read another 1000+ page book any time soon.

Getting back to Norman Davies’s impressive achievement, I would just like to share these awesome two paragraphs (WARNING: SPOILERS!!):

The collapse of the Soviet Empire is certainly ‘the greatest, and perhaps the most awful event’ of recent times. The speed of its collapse has exceeded all the other great landslides of European history — the dismemberment of the Spanish dominions, the partitions of Poland, the retreat of the Ottomans, the disintegration of Austria-Hungary. Yet it is hardly an event which calls for the historian to sit on the ruins of the Kremlin, like Gibbon in the Colosseum, or to write a requiem. For the Soviet Union was not a civilization that was once great. It was uniquely mean and mendacious even in its brief hour of triumph. It brought death and misery to more human beings than any other on record. It brought no good life either to its dominant Russian nationality or even to its ruling elite. It was massively destructive, not least of Russian culture. As many thoughtful Russians now admit, it was folly that should never have built in the first place. The sovereign nations of the ex-Soviet Union are picking up the pieces where they left off in 1918-22, when their initial flicker of independence was snuffed out by Lenin’s Red Army. Almost everyone agrees: ‘Russia, yes. But what sort of Russia?’

The most obvious factor the Soviet collapse is that it happened through natural causes. The Soviet Union was not, like ancient Rome, invaded by barbarians or, like the Polish Commonwealth, partitioned by rapacious neighbors, or, like the Habsburg Empire, overwhelmed by the strains of a great war. It was not, like the Nazi Reich, defeated in a fight to the death. It died because it had to, because the grotesque organs of its internal structure were incapable of providing the essentials of life. In a nuclear age, it could not, like its tsarist predecessor, solve its internal problems by expansion. Nor could it suck more benefit from the nations whom it had captured. It could not tolerate the partnership with China which once promised a global future for communism; it could not stand the oxygen of reform; so it imploded. It was struck down by the political equivalent of a coronary, more massive than anything that history affords.

Now that’s some beautiful writing, Jeff Pearlman.

No related posts.